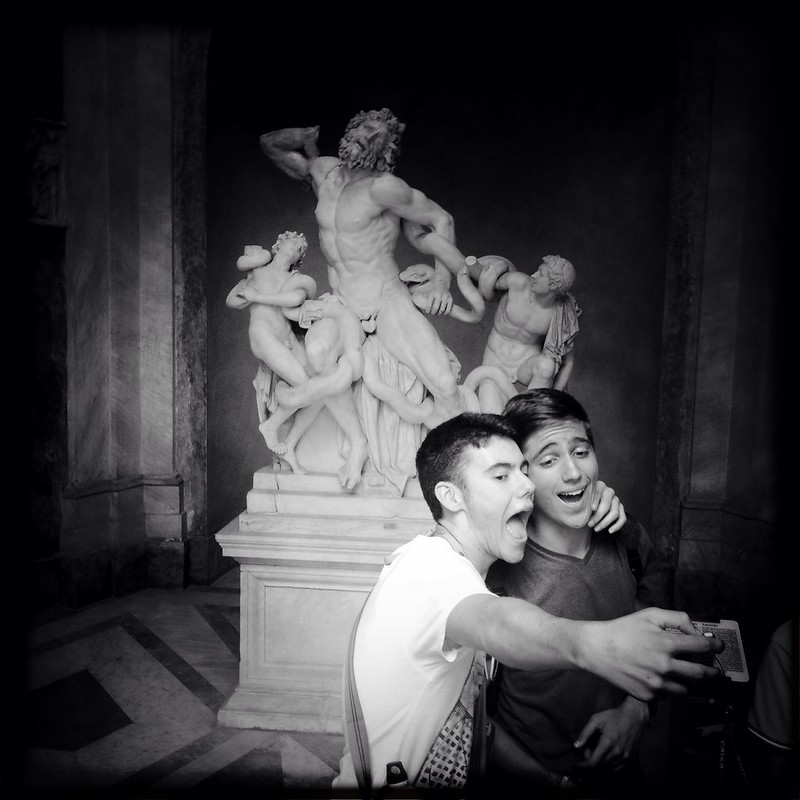

Vatican Museums, Rome

CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 image by Flickr user Fabian Mohr

Introduction

Visitors and their cameras. I thought I’d finished with this topic awhile ago. Visitor photography had been the third part of my Tilting at Windmills series, along with those other betes noir “immersion” and “participation”. I also wrote a follow up post of links on visitor photography for those really interested. The debate continues unabated, and as full of opinion masquerading as fact as it ever was. It’s grown to such epic proportions that MuseumsEtc is publishing a volume on museums and visitor photography. So, once more into the breach…

The National Gallery case

National Gallery, London

CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 image by Flickr user staticantics

The ostensible cause of the latest outburst was the National Gallery in London’s decision to allow visitor photography in August. One of the last “no photos!” bastions in Europe, the Gallery announced with no fanfare free Wi-Fi throughout the building, and tucked in with that announcement was a statement on their new photography policy.

Here’s what they said, as reported in the Telegraph:

“The introduction of free Wi-Fi throughout the public areas of the National Gallery is one of a number of steps we are taking to improve the welcome we provide.

“Wi-Fi enables our visitors to access additional information about the Collection and our exhibitions whilst actually here in the Gallery, and also to interact with us more via social media.

“As the use of Wi-Fi will significantly increase the use of tablets and mobile devices within the Gallery, it will become increasingly difficult for our Gallery Assistants to be able to distinguish between devices being used for engagement with the Collection, or those being used for photography.

“It is for that reason we have decided to change our policy on photography within the main collection galleries and allow it by members of the public for personal, non-commercial purposes -provided that they respect the wishes of visitors and do not hinder the pleasure of others by obstructing their views of the paintings. This is very much in line with policies in other UK museums and galleries.

“The use of flash and tripods will be prohibited, as will photography and filming in temporary exhibitions.

“Commercial photography remains subject to existing arrangements.”

Commence fireworks!

https://flic.kr/p/p5XtSX

Showa Kinen Park Fireworks Festival

CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 image by Flickr user yasa_

Not surprisingly, there was a lot of handwringing by journalists and bloggers who declared things like, “Camera phones at the National Gallery stoke fears that technology is leaving us incapable of deep engagement with anything”, and “Selfie-portrait of the artist: National Gallery surrenders to the internet”, and “Fears National Gallery will be ‘selfie central’ as photo ban is relaxed” And that’s just the mainstream media. You can imagine how the arts bloggers reacted. Eesh!

Within weeks, the chairman of the Arts Council, Sir Peter Bazalgette went on record supporting the idea of “selfie bans” for an hour a day, so people could get some relief from the hordes of picture snappers. And his was a fairly moderate opinion. The more absolutists were quite certain that doom was at hand.

Crowd Control 3

CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 image by Flickr user Son of Groucho

Sarah Crompton, writing in the Telegraph, describes the typical scene that those opposed to photography paint; the swarm of unheeding photographers, ignoring the real to capture the facsimile. Walter Benjamin’s warning made manifest. “A man who concentrates before a work of art is absorbed by it… In contrast, the distracted mass absorbs the work of art.” Crompton’s experience is similar,

“The last time I was in MOMA in New York, I fought my way up to the floor where all the masterpieces by Picasso, Matisse and the Abstract Expressionists hang – and then fought my way back out again. The space was full not just of viewers but of photographers; it was impossible to stop, think and look at a painting amid the jostling crowds.”

In the face of that kind of scrum, can any meaningful interaction occur? Apparently not. She concludes,

“By allowing photography, galleries are betraying all those who want to contemplate rather than glance. Surrounded by the snappers, they may come to think that this is the acceptable way to consume art, a kind of constant grazing without any real meal.

That’s not a means of making art more popular or accessible. It is the surest path to depriving it of all purpose and meaning.”

Judith Dobrzynski, in an uncharacteristically moderate tone, agrees that a ban is needed. One hour’s a bit too short for her liking, though…

Virtually no major outlet reported the National Gallery’s decision as a win for visitors, or a positive outcome in any sense. Even in the field, there was little mention made of it. And it’s easy to see why. Other people taking pictures, especially selfies, is easy to mock. Rather than explain this at all, you should just go look at Josh Gondelman’s piece in the New Yorker, “Works from the Los Angeles Museum of Photographic Self-Portraiture”. Pretty genius, huh? You’re welcome.

Two thoughts about the National Gallery

So, why so much vitriol, and what could the Gallery have done differently? For the first question, Nina Simon’s already addressed it, so I’ll focus on the second. But, first, Nina.

Deal with the real problem

Nina tackles the National Gallery issue in a post, entitled, “Blame the Crowd, Not the Camera: Challenges to a New Open Photo Policy at the National Gallery” which unpacks the whole thing so neatly and completely that I won’t waste many more electrons on it. In the same way that “immersion” and “participation” get used as straw men for deeper issues, “selfies” have become the stand in for the real issue at the major art museums where this problem is most often highlighted – overcrowding.

Crowded Mona Lisa

CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 image by Flickr user Iris

Read any of the writers advocating photography bans, and you’ll find them all mentioning crowding as part of the experience that ruins it. I agree that photography exacerbates it and makes more apparent how unappealing crowding is, but I think that visitor photography gets the blame for a problem that’s much bigger and harder to tackle. The experienced arts consumers may have given up on crowding as an unfixable problem, but I think it’s worth problematizing, rather than just taking it for granted. I dislike going to MoMA, or the Louvre, not because of the amateur photographers, but because they are like Tokyo subway cars, with art. How one deals with overcrowding is a totally different question than how one deals with cameras, and a solution to that bigger problem, I think, would probably resolve the smaller one. The responses to her post are as well worth reading as the post itself, so devote some time to it.

Don’t make a lemon out of lemonade

Looking over the whole affair, I think the National Gallery made a classic public relations blunder, and turned what was an unalloyed accomplishment to be proud of (introducing free Wi-Fi throughout the building) into a major media fiasco for one reason. They didn’t ever come out and say they wanted visitors to use their cameras. They essentially said “It’s too hard to monitor, so we’re not going to.” And that doesn’t reflect well on them, despite the obvious truth of it. And they reaped the whirlwind for it…

It *is* hard to tell what people are doing with their devices. Is that person taking a picture, or are they far-sighted and holding the phone at arm’s length so they can read their wretchedly small screen? Are they telling all their friends what a blast they’re having at the museum, or just searching for a new song to listen to because they’re bored? They all look pretty much the same, and anyone who thinks museums’ front line staff (who tend to be the least well-paid hourly workers) should make these kinds of fine judgements dozens or hundreds of times per shift all the while keeping an eye on the objects, fundamentally doesn’t get it.

Realistically, I think institutions have to clearly allow, or disallow visitors to use their devices, and whichever way they decide, they need to own that decision, and have it reflect the core values of the institution.

I’m totally down with the National Gallery’s decision to allow visitors to use their devices, because I think providing free Wi-Fi was a good thing. Making it as easy as possible for visitors to access information about the museum and its scholarship should be a major priority for all museums. One way you do that is by knocking down as many barriers to access as you can. One of those barriers, particularly in art museums, is the amount of interpretation provided. I think my next Tumblr may have to be “Art museum visitors looking at Wikipedia because the label didn’t tell them anything they wanted to know.” The Gallery produces lots of information about their collection, and should be commended for making it easy for visitors to access it in a way that is visitor-driven. But in doing that, they should’ve come up with a reason to either encourage or discourage photography. Allowing it was a half measure, and putting that half measure in writing was a bad idea.

The Frick Example

Frick Dining Room HDR

CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 image by Flickr user Paul Gorbould

It needn’t be that way. The Frick Collection in New York, had long been a no go zone for photographers. Like the National Gallery, they quietly reversed their photo policy in April, and a month later, reinstated a photography ban, saying this to Hyperallergic,

“After a brief trial allowing photography throughout the permanent collection galleries, it has become apparent we need to limit use of cameras to the Garden Court. The Frick Collection is virtually unique and especially valued for its lack of protective barriers, vitrines, and stanchions around works of fine and decorative art, displayed in a domestic setting. This refinement of our photography policy has been determined necessary to maintain the safety of our exceptional collections.”

And the hue and cry about this flip flop? Non-existant. The Frick totally owns their photography ban. It’s essential to the experience of seeing the objects in such a unique, unmuseum-y setting. They get full marks for being experimental enough to try to revise their policy. It shows they’re paying attention to what the outside world is like. And their reversal shows that they’re paying attention to the visitor experience and are willing to change based on evidence.

Mind your manners, not the technology

This evolving relationship with visitor photography and whether it’s good or bad has a lot to do manners and perceived lack thereof. The museums mentioned above both put explicit suggestions in their photo policies. The Frick’s used to read in part, “When taking photographs, please be courteous to other museum visitors by not blocking their views of artworks or impeding their movement through the galleries.” The National Gallery’s asked visitors not hinder the pleasure of others with their photography. But as Jillian Steinhauer wrote in Hyperallergic, when the Frick’s photography ban was dropped, “Pleas like these haven’t yet proven very effective, but maybe as photography in museums becomes less and less of an anomaly, we can shift our energy to figuring out how to do it right.”

Part of this dilemma also has to do with how we’ve conditioned ourselves to treat photography, no doubt based on older, analogue models of the process, when walking in front of a photographer meant possibly ruining one of a finite number of exposures on a roll of film that cost real money to buy and develop. Regan Forrest pointed me at an interesting dissertation that examined the visitor dynamics of photography in museums.

“It is the reflex action of trying to remove one’s self from, or trying to avoid the space between photographer and object. People duck and scuttle away, walk in reverse, stop and lean backwards or make an obvious decision to adjust their previously chosen path to circumnavigate the photographer and his or her line of vision to the object being photographed. Noticeably, the same behaviour does not occur if the viewer is not holding a camera in the process of taking a photograph. The viewer standing back from an artwork merely looking at it, is not afforded the same extreme actions of diversion as when a camera is involved. (Sager, J. F. (2008). The Contemporary Visual Art Audience: Space, Time and a Sideways Glance University of Western Sydney. pp174-175)

Our learned response to photographers is to give them wide berth, whether they ask for (or deserve) it. And we don’t seem to privilege looking at objects the same way. If you’ve had someone come stand directly in front of you to look at the object you’re looking at, you know the truth of this. And this where I think there’s really interesting room for engagement with our audiences.

Perhaps one of the best outcomes of all this angst will be some hard discussions around the visitor experience in museums and what factors contribute or detract from a good one. What should the current etiquette for museum-going be? What are the new rules of the road for having a rewarding experience engaging with our heritage? I’ll be looking at place like the Brooklyn Museum for inspiration.

Since this focused so much on the downsides of visitor photography, I’ll spend the next post looking at some positive examples of visitor photography in museums.

I visited the National Gallery last month, and was not aware that photography had just been permitted. To be honest, I didn’t find those taking photos to be a problem. The crowding – from photographers and non-photographers – were around the same high-profile works as before (i.e. Madonna on the Rocks and the Arnolfini portrait). I was more surprised by not being asked to check my bag, as I would have been at most North American museums.

LikeLike

Great point, Fiona. The hype versus the reality is important to keep in mind.

LikeLike

At the American Swedish Institute we actually have a designated “selfie station” in our August Strindberg exhibit. But it’s not there just so we can have a photo-op spot; it directly and purposefully relates to the exhibition’s theme of personal branding and crafting public image. In general we have a completely open photography policy, which elicits overwhelmingly positive reactions from visitors. (“Really? We can take photos? Awesome!”) But being much smaller than the National Gallery, we don’t usually have a crowding issue. And we see the photography policy as a part of our overall goal of providing “radical hospitality” to all who walk through our doors.

LikeLike

I went to the Louvre a couple years ago i’m sure it was where they had the Mona Lisa. Everyone on our contiki tour was told not to take photos inside the and strictly no flash. What happened? People were just sneaking photos in and a guy left his flash on and you can see a massive flash which annoyed me. I haven’t been to the National gallery but i couldn’t see why it would be different there.

LikeLike