by Flickr user Shareheads

CC-BY 2.0

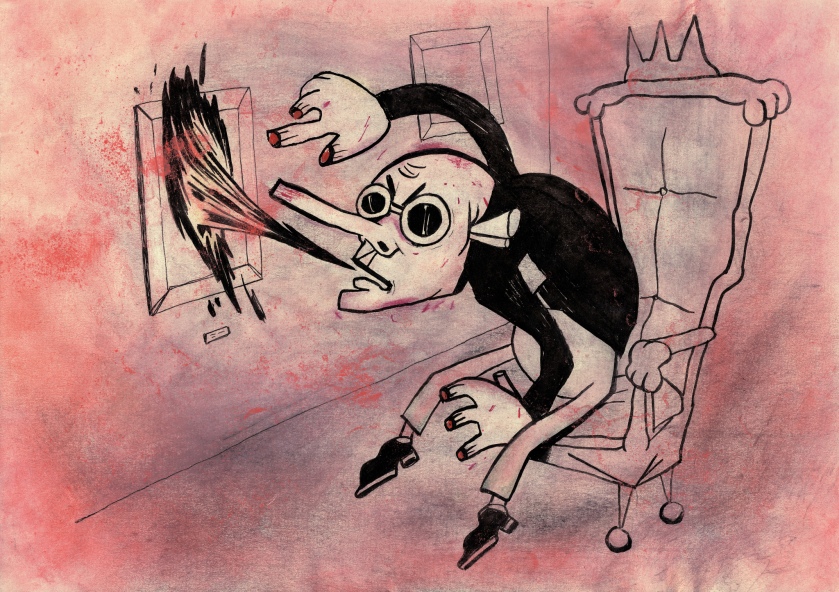

I have a confession to make: art critics baffle me. Especially when they venture to make grand pronouncements about the right way to go about experiencing art in museums. So when I saw the title of Philip Kennicott’s piece in the Washington Post, titled “How to view art: Be dead serious about it, but don’t expect too much” I will confess that I died a little bit inside. “Sigh. Another ‘you people are doing it all wrong’ piece.” Just what the world needs, another art critic holding forth on the sad state of museums and museumgoing. But, though there is plenty of sneering, there’s also a lot worthy of discussion. And debate. Kennicott’s post didn’t stand alone too long before Jillian Steinhauer posted a reply at Hyperallergic, and Jen Olencziak a rebuttal at Huffington Post. So, let’s take a dive in and see if we can sift some jewels from the bile, shall we?

Kennicott’s piece benefits most from his long experience at looking at art in museums. When he talks about specific techniques and strategies he’s learned that work for him, he’s golden. All too often, though, he falls prey to the critic’s kryptonite; thinking that because he can come up with a plausible explanation based on purely on anecdotal experience and write it cleverly, it must be both true and universal. So, here are some reactions to his five tips on how to view art in a museum.

1. Take time

by Flickr user Byron Barrett

CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0

“The biggest challenge when visiting an art museum is to disengage from our distracted selves.”

Getting visitors to focus on the present is a goal I’m totally in support of, though I’d rephrase Kennicott’s phrasing. I’m prone to these kinds of negative formulations, and it’s been a lifetime’s work to embrace positive ones. It may seem like splitting semantic hairs, but I think it’s important. Rather than disengaging from a negative (busyness and distraction), I’d rather encourage engagement with the here and now as the goal. It’s a lot easier to be against something than to be for something, but being for something is in the end more worthwhile.

<snark>My inner cynic also thinks that being an art critic, Kennicott might be allergic to the word “engagement”, since it’s code for some for “everything I hate that our ‘stewards of culture’ do with audiences that doesn’t encourage silent, solitary, reverential contemplation.”</ snark>

“We are addicted to devices that remind us of the presence of time, cellphones and watches among them, but cameras too, because the camera has become a crutch to memory, and memory is our only defense against the loss of time.”

Here he’s conflating two very different problems; devices demanding attention, and cameras being crutches for remembering, and therefore bad. The device bit I agree with. By all means turn off your phone, or put it on vibrate. Unless you don’t want to. <snark>Or if you’re using it to look at Wikipedia to find information the museum doesn’t tell you, which Kennicott will encourage you to do in the next section. </snark> The camera/crutch formulation deserves a bit more examination. The “ technology is eroding our ability to use our minds” is an old trope. And I mean old, like 4th century BCE old. At least. According to Plato, Socrates warned against the written word as a shallow substitute for discourse:

“this discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves. The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality.”

Sound familiar? You can draw a line from Kennicott back to Socrates and find versions of this concern expressed for any number of technologies that were certain to ruin humanity’s ability to function.

by Flickr user Snapshooter46

CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0

He goes on to say,

“The raging debate today about whether to allow the taking of pictures inside the museum usually hinges on whether the act of photographing is intrusive or disruptive to other visitors; more important, the act is fundamentally disruptive to the photographer’s experience of art, which is always fleeting.”

So, anything that isn’t looking at the art is “fundamentally disruptive”, according to Kennicott. Is it? Readers might recall an article published in Psychological Science earlier this year called “Point-and-Shoot Memories: The Influence of Taking Photos on Memory for a Museum Tour” which was used by many to support the idea that photography was bad for the photographer’s recall. Linda Henkel’s experiment generated a lot of breathless press and finger wagging when it was announced that participants who were instructed to photograph an object and then asked to recall it the next day fared worse than visitors who were instructed to look at the object and recall it.

Buried in there were two important notes that went largely unreported. One was that visitors who photographed specific details of an object had better recall than visitors who just looked. The other was Henkel’s admission that the way the experiment was constructed had an important difference from the way people actually take photographs in museums. Henkel’s subjects were told which object to photograph, not to pick an object they liked. In other words, they were extrinsically motivated, not intrinsically motivated, which is a fundamental aspect of free choice learning. I’m pretty confident there aren’t many visitors running around taking pictures of things they don’t like in museums. This difference in motivation is fundamental.

Another, “your mileage may vary” sort of issue is that of mission. If a museum’s mission is exclusively to showcase the artistic production of others, then anything that gets in the way of that appreciation could legitimately be considered an impediment. But more and more museums have taken of the additional challenge of encouraging visitors to express (and hopefully increase) their own creativity. In this kind of museum, visitor photography can be an expression of that creative impulse to be encouraged and nurtured. There’s an interesting discussion for museum directors and boards to have. Are you trying to help your visitors become more informed connoisseurs, or give them more experience of the creative process? Is it one or the other? Are the two modalities in a dialectical relationship, or can you encourage both?

Kennicott buries one zinger I particularly resonated with at the very end of this section; the negative impact of admission fees. He calls them “pernicious” because “They make visitors mentally ‘meter’ the experience, straining to get the most out of it, and thus re-inscribe it in the workaday world where time is money, and money is everything.” At moments like this, I appreciate his command of the language. And I agree completely. I’m sure most of us have seen the hurrying tourists, desperately trying to see all the highlights listed in the guide, so that they can get their “money’s worth” out of their trip. Not something we as museum professionals want to encourage, is it?

So, by all means take time, and use that time to be present in the moment, in that space. This is actually good advice for life in general, not museum going, but that’s another subject altogether.

2. Seek silence

by Flickr user Jrm Llvr

CC-BY 2.0

“Always avoid noise, because noise isn’t just distracting, it makes us hate other people.”

One reason I have difficulty with a lot of criticism is that I wind up feeling like I know more about the critic than I ever wanted to, because so much criticism wraps personal quirks in the garb of universal truths. Noise can be annoying, sometimes. As a neuroscientist pointed out to me yesterday, the way we experience visual inputs and auditory inputs is very different. If you see something you don’t want to see, you can avert your gaze, or close your eyes. Humans have no similar way to filter out auditory inputs. Even blocking your ears is only minimally effective (and makes you look kinda silly), so a valid criticism of museums could be how poorly they design the experience for sound control. This is all, of course, assuming we’re talking only about visual arts.

Big, echoey spaces with hard walls and floors look sweet, but they make even small levels of noise problematic. We’re on the verge of opening a major video installation PEM commissioned. The amount of work we’ve done modifying acoustically “bright” galleries work for an installation that requires you to be able to hear spoken words is pretty major.

“Too many museums have become exceptionally noisy, and in some cases that’s by design. When it comes to science and history museums, noise is often equated with visitor engagement, a sign that people are enjoying the experience.”

Where to begin with this one? I’m pretty confident that there are very few museum architects and experience designers who intentionally create noisy spaces. I would not be surprised if the number were in fact zero. An outcome of their decisions might be noisy spaces, but that’s different than intentionally doing it. This is another favorite tactic of critics, inferring intent where none exists. <snark> Maybe that’s another one of the deceptions (see #3 below) practiced on the public by museums. </snark> It’s sloppy thinking and writing.

I’ll also hazard a guess that the number of museum professionals who go into a space and say “It’s noisy, people must be engaged” is also quite small. Kennicott, like most critics, avoids mention of the real problem Nina Simon mentioned in this post on crowding. He laments the “vast and inevitably tumultuous throngs” that go to big museums to see famous art, but leaves it there.

by Flickr user mesh

CC-BY 2.0

“But any picture that attracts hordes of people has long since died, a victim of its own renown, its aura dissipated, its meaning lost in heaps of platitudes and cant. Say a prayer for its soul and move on.”

Umm… Yeah, OK. So art must be unpopular to some extent in order to retain its “aura”?

Nobody better tell the Louvre.

3. Study up

by Flickr user NCinDC

CC-BY-ND 2.0

“One of the most deceptive promises made by our stewards of culture over the past half century is: You don’t need to know anything to enjoy art.”

A theme throughout this piece, and a lot of criticism posits an alternate reality where museums willfully and systemically deceive and injure the visiting public by “pandering” “surrendering” and “succumbing” to malignant forces in the larger culture. The reasons vary, though incompetence, and venality often appear as root causes. In their unbridled lust to get bodies through the doors, museums say and do anything to be popular. Like awkward teenagers, desperate to fit in and be liked, despite their unfashionableness, they make deceptive promises that ultimately do a profound disservice to the visiting public and to the art that museums allegedly steward for future generations. Note the plural. What we’re discussing here is but one of many deceptive promises. I have to wonder if Kennicott has ever shared any of his theories with a real live museum staff person.

“Our response to art is directly proportional to our knowledge of it.”

I agree with this statement, but in a way that I think undermines Kennicott’s central assertion. I have previously written at length about a visit to the Museum of Old and New Art in Hobart, Tasmania. Read them here, here, and here, if you want more information. It’s a great place to visit if you’re at the bottom of the world. One of the conceit’s of the museum is that there are no printed labels. None. Zero. All the interpretation is carried in an iPod you are given when you enter. In the midst of a profoundly transformative visit where I was forced to look at the art, not the interpretation, I came across a smallish painting that looked like a poorly copied Picasso. I registered my dislike of the object and, on a whim, looked up it’s information only to find that it was in fact a Picasso. I had the realization that had there been a tiny tombstone label identifying the work as such, I would have unable to dislike that object as much because of the associations I already carry around about the canon of Western art. Just seeing

Picasso, Pablo Spanish 1881-1973

would’ve colored my emotional response to the work in front of me, and Picasso’s stature in the canon would’ve influenced my feelings about that painting.

There is a place for showing, and a place for telling, and there can be an order in which they happen that allows visitors to have both the direct experience and the received wisdom, without either oppressing the other.

The pendulum, for decades lodged at one extreme, has swung towards the opposite pole, and I can understand Kennicott’s displeasure, but it’s the displeasure of the entitled, seeing others’ needs and comfort placed ahead of his own for a change.

“art is the opposite of popular entertainment, which becomes more insipid with greater familiarity.”

<snark> My sons will doubtless agree with this. Their appreciation of Pokemon never waned. No matter how many times they saw Jessie and James get flung into the sky, it was magic each time. Ditto for Thomas the Tank Engine. </snark>

“Even 10 minutes on Wikipedia can help orient you and fundamentally transform the experience.”

Sounds reasonable to me. I think Wikipedia offers a great challenge to museums. A visitor can access content about just about anything on a mobile device these days. The fact that so many do access content like Wikipedia in museums should tell experience designers something. Their content is either lacking, or not the information visitors are looking for. So, what to do? I can think of a number of strategies for addressing the problem, all of which would result in experiences that do not feature objects with tiny tombstone labels near (but not too near) them.

“If the guide spends all his or her time asking questions rather than explaining art and imparting knowledge, do not waste your time. These faux-Socratic dialogues are premised on the fallacy that all opinions about art are equally valid and that learning from authority is somehow oppressive.”

I get the feeling Kennicott’s not a fan of Visual Thinking Strategies, and that’s OK. Declaring them “faux-Socratic” and fallacies, is not. Unless he has evidence and research to back up the claim, it’s just another example of the “I came. I saw. I invented a narrative that suits my worldview.”

4. Engage memory

by Flickr user Sam Burns

CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0

“Unfortunately, unlike most things we study and debate, art is difficult to summarize and describe.”

Part of me would love to know what those easy to summarize and describe topics are. Most of my experience with experts in any field is that the more they know, the harder it is for them to summarize and describe what they do.

“Some museum educators, who know these things, will tell you this kind of detail doesn’t matter; they are lying. Always try to remember the name of and at least one work by an artist whom you didn’t know before walking into the museum.”

Back to the conspiracy theory and the museums actively disseminating falsehoods. Sigh… Actually, if the educators believe what they’re saying, they’re not lying. They’re expressing an opinion that conflicts with Kennicott’s. But in his mind, that is obviously the same thing.

5. Accept contradiction

by Flickr user Tjook

CC-BY-ND 2.0

“Art must have some utopian ambition, must seek to make the world better, must engage with injustice and misery; art has no other mission than to express visual ideas in its own self-sufficient language. As one art lover supposedly said to another: Monet, Manet, both are correct. “Susan Sontag once argued “against interpretation” and in favor of a more immediate, more sensual, more purely subjective response to art; but others argue, just as validly, that art is part of culture and embodies a wide range of cultural meanings and that our job is to ferret them out. Again, both are correct.”

Except he’s already made clear that agreeing with Sontag is both wrong and bad. Kennicott’s willing to give lip service to accepting the kind of contradiction, but nothing substantive.

And to tie it all in a nice neat bow, he ends with:

“Some practical advice: If you feel better about yourself when you leave a museum, you’re probably doing it all wrong.”

All those years of museum going on my part were wasted, apparently. Oh well…

Next up: A look at some of the responses to the Kennicott piece.

Thanks – this past week I’ve been on a long slide from Tiffany Jenkins’ piece, to this one, to the responses. I share many of your reactions.

The contempt for educators is fairly grating. It’s not just VTS that he’s objecting to (VTS is just one tool in the toolbox, and a fairly specialized one that we don’t lean on too heavily) but the very premise that anyone other than the docent should be talking on a docent-led tour. Much as many docents themselves enjoy that model best, it’s not good teaching practice. One of the fundamental principles of andragogy (adult education, as theorized by Malcolm Knowles in the 1970s) is that an assembled group of adult learners is rich in experience, and that effective adult learning must connect to and mobilize that life experience in service of the group’s learning goals. Without conversing, you condemn the group to operating at a lower intellectual level than they otherwise would, and cut off the opportunity to learn from one another. Doing this well means having skills in facilitation that allow the group to pool and share knowledge and observation, and also to identify the useful and appropriate moments to layer in didactic information. I can agree with critics that not every docent/educator/facilitator does this to the highest possible standard all the time. That can be a very real selection, training, and management issue. But that doesn’t make the goal – interpersonal interactions with one another and museum staff that produce meaningful and memorable experiences with objects – wrong in itself.

I generally feel that contempt for this kind of educational discussion is really privilege disguised as concern. An independent learner who already has a strong command of information and has already identified exactly what they do and don’t want to know about objects doesn’t see a value in this process; but people like that are in that moment different from people who do see a value and benefit from these interchanges. In fact, people like that are probably best off with an iTunes lecture or curator-led audiotour, because they are not going to make the most of the responsive and interpersonal resources of a guide and a group. It is a kind of privilege to feel that you should be able to use the museum without sharing it with others, and a kind of privilege to esteem your own style of appreciation and learning as more appropriate than others’. It is probably uncomfortable to be pushed away from the center a bit, because, to be fair, for most of the past century museums have colluded in allowing that kind of privilege to reign as the default experience.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Privilege disguised as concern” is well-put. I’d also add “Fear masquerading as scorn” as one of the overriding vibes of these kinds of op-ed pieces.

LikeLike

Ed, thanks for the detailed and insightful response to Kennicott. I especially enjoyed the museum photos you sprinkled throughout the post — one of my little hobbies (or guilty pleasures) has always been to search for such photos on the internet, and you found some real jewels.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Mike! I will confess to doing double duty with the photos. My Tumblr was in need of some attention, so People Behaving Appropriately in Museums will get some fresh content.

P.S. However I mistyped “Mike” the first time, it autocorrected to “Camille”. Ponder that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoyed your analysis very much – I will go and read the original piece (although I suspect I won’t agree with it veyr much either). Your mention of the Museum of Old and New Art having no labels on the works reminds me of the Isabelle Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, which also has no labels with the exception of the works that had labels in the works’ original frames. (It also has laminated room maps in a rack in each room). I found it a very different experience to visit a museum like that, and if I recall correctly Mrs. Gardner set it up that way for exactly the reason you describe – so that visitors’ experience of the art wouldn’t be mediated by knowing right away who the artist was.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly! A lot of these debates paint a dichotomous view of visitor experience. It’s either A or B, and if it’s one, it can’t ever be the other. MONA, the Gardner, and others offer the possibility of a third way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Marketing, Interaction & Technology and commented:

Excellent post by Ed Rodley in response on a critic’s explanation of how to look at art in museums.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a great response post. I enjoyed your references to Plato and Socrates!

I’m by no means an authority when it comes to art within the walls of a museum but Kennicott’s article struck me as a contradiction to what many artist’s believe their art stands for (and it’s not restrictive learning or one way fits all type of viewing).

Personally, I’ve learned plenty from viewing art pieces first and then researching afterward. We all have different personalities and learning habits. I can’t speak for all artist’s but many of the artist I know create art to communicate their worldview and/or perception about a matter (subject, event, object, etc). They also don’t mind people snapping pictures at their art – they’re very generous with their art and flattered when people would take the time to snap a picture for the go or to share with others.

I took a look at some of the most recent comments on Kennicott’s article and many agree with this blog post. If he would have prefaced his article with listing methods he’s found to work for himself, then maybe people could have expanded on his article instead of being so bothered by it.

Thanks for posting your analysis! Looking forward to reading more of your posts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Luis.

I agree that a lot of the negative response to Kennicott’s piece could’ve been avoided if he could’ve made the piece about how *he* views art, and not how *everybody* should view art.

LikeLike

Love your balanced take here!

I don’t put too much stock in Kennicott’s views. He has good and bad writing days–for an example of exceptionally puerile writing, see link to is his review of “The Monument’s Men”

http://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/george-clooney-saves-puppies-from-nazis/2014/02/06/d9e5a218-8a8e-11e3-916e-e01534b1e132_story.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

I already left a comment but I just read an article written by Stephanie Rosenbloom for The New York Times and wanted to share it. What a difference in tone compared to Kennicott’s article!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Museum Avenue.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very clever and ironic, truly vvid style!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pas mal ton blog

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love the picture! Art can be everything you want it to be, and I want it to touch me. I liked the part about engaging memory. We should all do that more!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was really interesting, as I recently visited a couple of galleries which I haven’t done in a while. I love the light yet thoughtful way you approach this topic. The final point, that if you come out feeling better about yourself then you’ve got it all wrong…well, that made me laugh out loud. Truly. I’m looking forward to reading more about this as you look at the responses. Thanks for so generously sharing such a well researched, well written piece. Blessings, H xxx This was my own response to visiting a gallery recently – I must’ve got it all wrong…http://wordsthatserve.wordpress.com/2014/10/12/the-art-of-ritual-and-reverance-a-good-deeds-post/

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think viewing the piece and feeling kinda humored by it, is exactly the response the article needs. Keep enjoying art if that works for you!

LikeLike

Great post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on elnuevoeuropeo and commented:

I completely agree..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on fine art photo a love story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for unpacking the info on the Henkel experiment. I had meant to read up on it so was glad to catch the summary here. Great choice of photographs that add to the post, which brings another point . . . making art from art and how does that change the viewer’s perspective? Had some fun with that: http://psalmboxkey.com/2014/01/09/mea-culpa-breaking-the-rules-at-the-art-museum/.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad it was useful to you! I really get steamed when folks take one point out of a research study and run wild with it. It’s not like it’s a long article with thousands of figures and graphs to interpret. It’s pretty straightforward. I’ll check out your post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

My favorite was this quote: “But any picture that attracts hordes of people has long since died, a victim of its own renown, its aura dissipated, its meaning lost in heaps of platitudes and cant. Say a prayer for its soul and move on.”

So “it’s popular, therefore it sucks”, right? That’s an old idea cultivated by the kinds of people who love to drop the names of obscure artists and bands to show off how cultured and in the know they are. But Kennicott’s not just saying “it sucks” – he’s saying “it’s meaningless”. How the hell does that follow? Have works like Guernica or Third of May 1808 lost all their meaning just because they’re famous? Does that mean a great painting that only one other person has viewed has the most meaning of all? Logic!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yup. Yup. And yup.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on cynix9 and commented:

Masterpieces speak to a few a day or a group of wandering tourists. An artist’s precipice is of no article in gesture..to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I recall some of my best museum visits being the exact opposite of these advices. Briefly viewing several museums in a few hours, not lingering on an object longer than I felt necessary to get an impression, with loud music in my headphones setting the pace and a background atmoshpere (punk and/or techno work best for me), with zero preparation up front, not remembering anything about the artists or the art, just getting raw impressions, not being philosophical about the art or trying to become a better human but just admiring one inventive product of the human mind after another.

My point is – there are many ways to view art. Probably as many as there are people in the world multiplied by the number of moods a human can have. And when someone is saying to me that there is a “right” and “wrong” way to view art, then I think that my and their view of art, its definition and purpose, are fundamentally different.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sooo insightful as always, Ed. And on the whole & with the particulars I have similar issues with the original post, and agree with so many of your points.

Having recently done a chockablock 2 days of museum-ing (4 museums and 2 extraordinary public art exhibitions) in Basel, I broke Practucally all of Kennicott’s rules, and had the most delightful time. I pulled my phone out several times, not to be distracted but because I was so blown away by a new artist I had never heard of that I HAD to capture his name and details for later; I was lucky enough to walk through a gallery of early 20th century photography with a couple who were not silent, and whose conversation opened whole new areas of interpretation I never would have gotten to, no matter how much studying up I might have done in advance.

I will concede that accepting contradiction is a good one; I am right with him on that. But “if you feel better … you’re doing it wrong” is just ludicrous, and borderline insulting. Overintellectualizing yourself out of the opportunity to just feel pure joy may be a critic’s bread and butter, but no thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Basel, eh? What did you see? Anything good?!

One of the challenges of writing this response was that I do agree with a lot of his assertions. Taking time, accepting contradictions, focus; all of this stuff I agree with as good skills to possess. Even being willing to be made to feel deeply unhappy by art is something I think we should be alive to. Art doesn’t just exist to make us feel good. And criticism doesn’t have to be so curmudgeonly that it makes a virtue out of feeling bad.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on ARTE, SIMPLESMENTE….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Apps Lotus's Blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Super Storm News.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Engineer Marine Skipper.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Smithy 3333.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Illumination.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Its a BVS world and commented:

Very interesting! Excellent topic and illustrations.

LikeLiked by 1 person